* UKRAINE WAR - Mario's in Kyiv is published during the height

of the conflict, featured in the Kyiv Post.

If above link doesn't work, a pdf of the poem is provided here.

* * Mario's IIWW poetry featured in the 2014 Bloodaxe Anthology,

"The Hundred Years’ War: modern war poems" [click here].

Mario provides specialist talks & class workshops for all war syllabuses, including 'AS AQA ENGLISH LITERATURE A' syllabus [Option B: 'World War One Literature']

CONTEXT NOTES for the POEM by Mario Petrucci. "The Western Front 1914 to 1918 left a profound wound in our species. Trench Warfare created unimaginable contrasts between the best and the worst of humanity:

intolerable collective brutality, and astounding individual sacrifice. ‘Strange Meeting’ is among the most moving and haunting poems of the First World War. A hundred years on, Owen’s words are still unsurpassed in their complex power and (in spite of his subject matter) their linguistic and formal richness.

Through his eyes, we see again the ultimate failure of war, its utter futility. At a time when modern warfare can sometimes resemble a computer game, Owen puts us face to face with the ‘enemy’.

He leads us into an underworld where we are all accountable (symbolically, if not actually) for the actions of our representatives in conflict, where fallen combatants have at last a chance to exchange heartfelt words, to lock eyes in the midst of nightmare and speak their dreams, their truth."

STUDY NOTES for the POEM by Mario Petrucci. "This video provides a superb resource for teachers in the classroom who wish to bring the poetry of the First World War more fully to life. It introduces powerful and provocative material, for group discussion and individual contemplation alike.

Whether or not this particular poem is included in your curriculum, syllabus or exam, its relevance to the study of poetry more generally is easily established. Owen's use of form, for instance, is both lyrical and unsettling, and the ideas and metaphors he stitches through the fabric of the poem are of a rare order.

It is, finally, deeply informative (as part of your literary studies or your analysis of poetry) to compare this poem to some of the more conventional verses that were commonly written during The Great War. Indeed, Owen's extraordinary piece makes a top choice for any 'Compare and Contrast' exercise of this kind.

One subtle technical aspect of this poem is the way Owen rhymes words or syllables 'front and back', creating a disturbing yet profound ongoing sonic effect: groined/groaned, hall/Hell, grained/ground, moan/mourn, years/yours, wild/world, spoiled/spilled, mystery/mastery, world/walled, war/were, friend/frowned, and so on. [How many more of these can you find?]

This is a remarkable example of what I (more generally) call 'sonic stitching' in a poem. For this particular sonic effect, though, as used here, the usual technical term is 'pararhyme', and Wilfred Owen was one of its first major exponents. In pararhyme, the consonants either side of the central vowel 'agree', but the central vowel itself differs.

This is a brilliant move on Owen's part: to utilise a sonic device that comes close to rhyme, but that feels vaguely 'off' or 'wrong'. In his poem, the completeness of a 'hard' [or ‘full’] rhyme is withheld, denied. Ask yourself: how does this technical effect underscore the subject matter – and the overall mood – of the poem?

Moreover, the fact that Owen used this near-rhyming device so insistently in his poem and yet still somehow manages to maintain the sense of an ordinary speaking voice (with all its authentic emotion kept intact) is nothing short of genius."

Feedback on AQA lectures & student workshops (War Poetry):

"You had them falling over themselves to praise your session. They were enthusiastic about everything, your talk, your notes and the involvement of the students. You provided a great deal of food for thought and ideas for follow-up work. Thank you for another outstanding session." (Institute of Education, organiser comments, 2010)

"Very engaging, clear, focussed, delivered in a sympathetic and accessible manner." "Excellent. Concise, not just talking at us." "Fantastic, dynamic and engaging." (Institute of Education, Teacher feedback, 2010)

"Thank you for taking the trouble to make your talk interesting and appropriate for first year A-level students. What comes through from the teacher feedback is that your talk worked both for them and their students and that you managed to make it both accessible and stimulating." (Institute of Education, organiser comments, 2008)

"Your magic touch... a perfectly-pitched, interactive session which made the students actively think. They enjoyed your in-depth examination of poetry before and after the war and seeing/hearing your varied resources, to help them explore context... plenty for them to take away to the classroom and put into practice for their examinations." (AQA event at Imperial College London, organiser comments, 2017)

'High Zest & the Doggerel March'. For AQA teachers & students... some essential patterns and myths concerning Wilfred Owen and our understanding of IWW Poetry pamphlet here

'Strange Meetings: an evening of War Poetry with Mario Petrucci'. Special Edition series: 6 August 2014. Southbank/ Saison Poetry Library.

'Voices from the War'. Click here for brief audio of the interview given by Mario prior to the 7 May 2015 'Poet in the City' IWW event held at The Old Town Hall in Richmond (London). (The event in its entirety was itself recorded for audio archive by the British Library.)

[If the Poet in the City link given above is down, &/or to listen to the author's re-edited version of this audio, click here - by kind permission & for archive purposes only.]

Some examples of Mario reading his war poems: Nightwalker [inspired by trench poet Ivor Gurney]

; Soldier, Soldier.

Residencies - IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM

"A contemporary poet who writes and speaks passionately

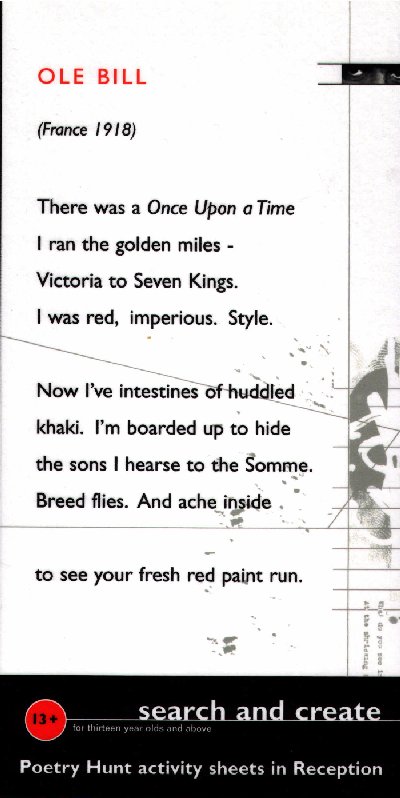

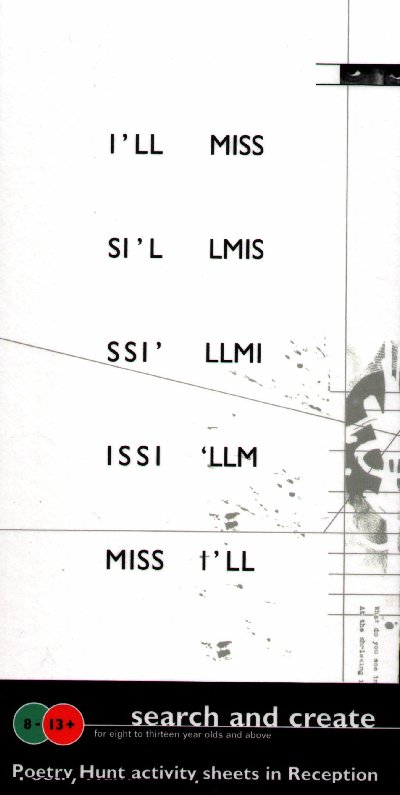

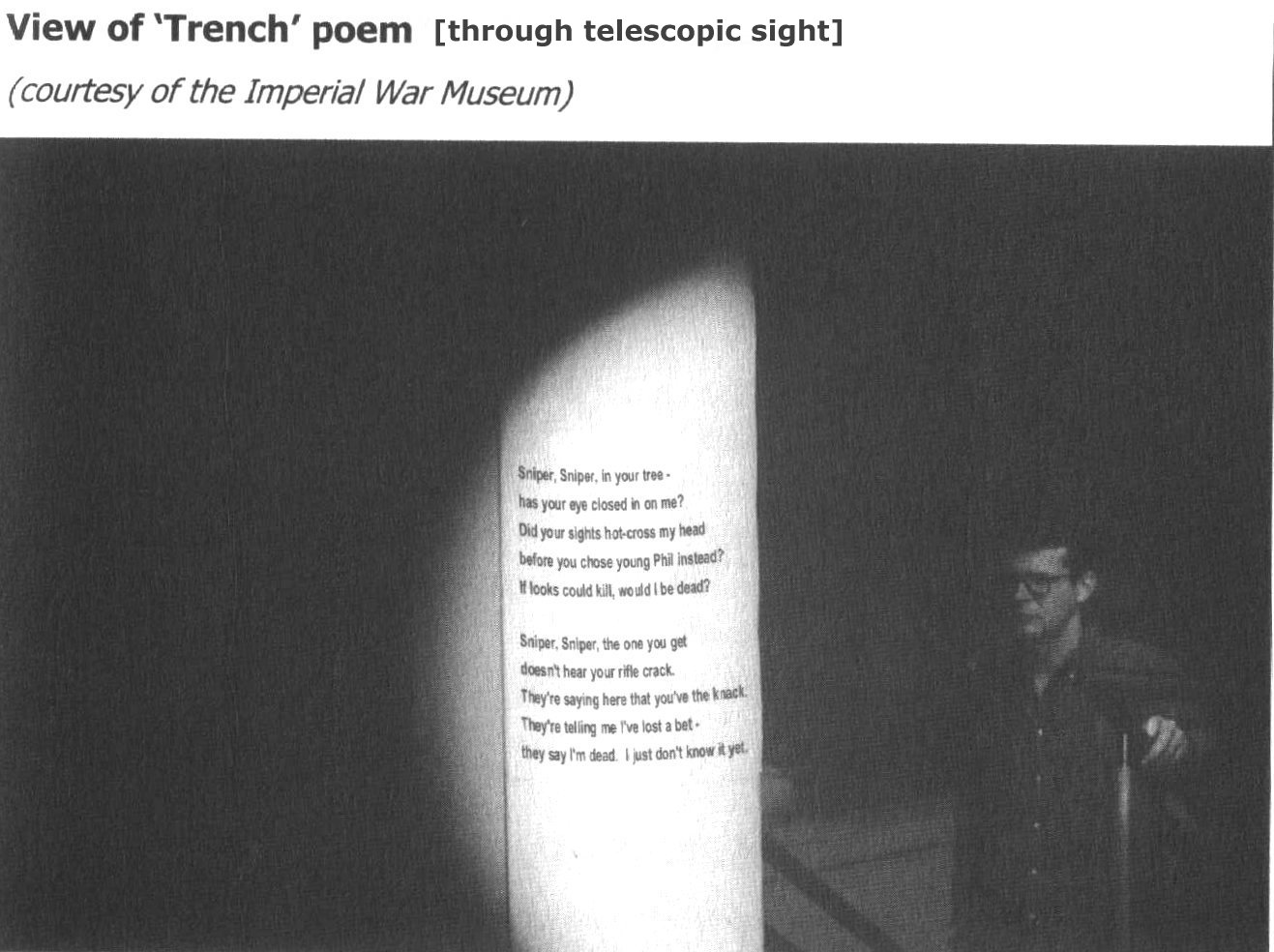

One of the fruits of this project, Search and Create, was a long-standing, low-profile 'poetry hunt' suitable for all visitors (though it was designed to be of particular interest to schools).

Invented and implemented by Mario through the early stages of his residency, Search and Create could be found (after some searching!) throughout the Large Exhibits Gallery and Balconies at the Lambeth Road site.

It was a distinctive and popular installation, surviving many years until its removal as a result of the Museum's major refurbishment completed in 2013.

The composition and (canny, often provocative) placement of his poems served to multiply and expand the context of their associated artefacts and locations, to facilitate a much wider, richer range of viewer response.

Petrucci termed this concept 'Multicaptioning'; it forms a keystone of his efforts to develop a textual-visual 'literARTure' in museums and other public spaces.

The poem Negatives, written by Mario during his very first day at the Museum whilst being 'inducted' through the photographic archives, subsequently won the prestigious Bridport Prize.

He has been commissioned to invent Multicaptions at the Cabinet War Rooms [now 'Churchill War Rooms'] and with IWM North in order to generate new kinds of visitor/family response.

He is the Museum's official Literacy Consultant and frequently teaches war poetry at the Museum (with Jon Stallworthy) for visiting schools and teachers.

CLICK HERE. . .

CLICK HERE. . .

"Petrucci's poems deal with the emotional condition of war, the suffering... The effect of these tiny poems placed next to enormous pieces of metal

* LiterARTure: principles of visual art embedded in the text and its creation - or - literature/text contextualising and framing an artefact.

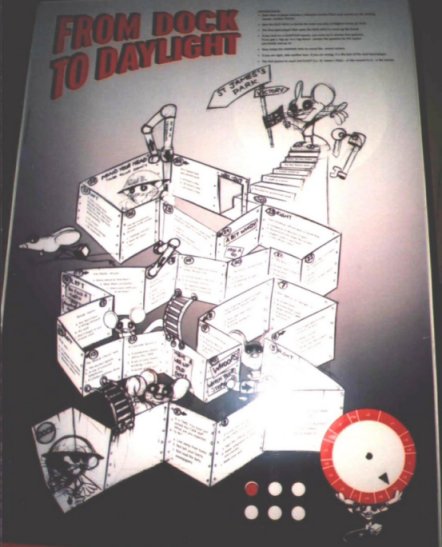

'Dock to Daylight' game for children at the Cabinet War Rooms.

CLICK HERE to play the 'Dock to Daylight' game!

Poetry Hunt ...

WAR POETRY for classroom & curriculum...

using set texts Up the Line to Death (Brian Gardner), Scars Upon My Heart (Catherine Reilly), The Oxford Book of War Poetry (Jon Stallworthy).

Click here... to hear Mario reading Wilfred Owen's Strange Meeting,

commissioned for the Royal Festival Hall - Poetry International festival, July 2014

(by kind permission: Saison Poetry Library/ Mario Petrucci, 2013) or watch the YouTube video below...

- also, audio of groundbreaking sixth-form lecture 'High Zest' (available here), part of Petrucci's extensive Imperial War Museum poetry residency archive (© IWM; extract used here by kind permission, not for commercial reproduction).

OTHER WAR-RELATED EVENTS & TEACHING...

The World Wars represent crucial turning points for our civilisation. The unprecedented psychological and material upheaval meant that poetry could never again rest on its Georgian laurels – or did it? In a presentation that bristles with provocative insight, Petrucci guides us on an unexpected journey through the poetry of WWI and WWII,

introducing us anew to those war poets we have come to admire but also, just as poignantly, to those of immense influence who are now long forgotten. Utilising original recordings and live recitation, Petrucci conveys the poets’ messages directly, generating a powerful and intimate experience of war poetry.

[A full recording of Mario's talk is held at both the Saison Poetry Library and the British Library.]

[Repeated: 4 Nov. 2014, by popular demand.]

* * *

and searchingly about the social impacts of war" - Imperial War Museum

Multicaptions / LiterARTure *

Initially supported by the Poetry Society's Poetry Places scheme, Mario Petrucci has been engaged in a long-term association with the Imperial War Museum across its several sites.

An early indication of the strength of this association is that the Imperial War Museum itself conferred upon Mario the honour of officially becoming its first ever poet in residence

is powerful. Placed in intriguing places, like the treasure at the end of a hunt, these poems achieve something more complex than the pleasure

derived from finding what one is already searching for. They produce an atmosphere of disquiet." Jane Rendell, Art & Architecture (2006).